Philemon’s Photographs or Through an African Lens (Laura Horelli, Philemon Sheya Kaluwapa) 2022-23

Philemon Sheya Kaluwapa’s black-and-white photo album from the early 1980s frames the content of the film. The album contains photographic exercises made during his training as a photo technician at Foto DEWAG in East Berlin. Kaluwapa received a scholarship from the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED), which supported the South West Africa People’s Organisation (SWAPO) in its struggle against the South African illegal apartheid regime. The placeless photographs, shot mainly in a studio setting, stand in contrast with Kaluwapa’s exile from Namibia in 1974 and his movements through various cultures, countries, and political systems.

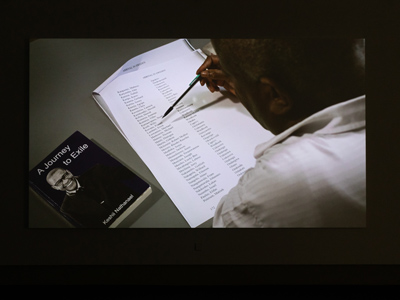

Laura Horelli and Philemon Sheya Kaluwapa initially met through Horelli’s installation and short film Namibia Today (2017–2018) and have continued discussions ever since. Kaluwapa asked Horelli whether she could help him write his memoir. Horelli answered that she could not write a classical book, but she could try to develop biographical fragments into a film. Kaluwapa introduced Horelli to photographs he shot in East Berlin, including those of his study mates Nangula and Haufiku. From here, the authors developed a film, set in a photo studio to mirror the original setting of the photographs.

The film takes on several narrative strands, including Kaluwapa’s interest in how he could best use the medium to portray Blacks and his experiences in the African diaspora and the Cold War—particularly his pivotal decision to flee from East Berlin to West Berlin. The two-part title Philemon’s Photographs or Through an African Lens refers to the different but co-existing perspectives, identities, and motivations in making this artwork.

The dialogues were scripted, but the conversations often took their own course during the shooting. Scenes with synchronised sound were combined with voice-over recordings resulting in an open form, a sort of experimental documentary. The predominant language of the film is German because both Kaluwapa and Horelli have lived in Berlin for a long time. Both speak German as their third language, adding migrant perspectives to the work. The choice of language, however, gains another dimension when seen in the context of German colonial history in Namibia.